Introduction

Henry VI was England's youngest ever monarch, becoming king at only nine months old. As a baby, he was clearly not a statesman, and so for his medieval subjects it was his lineage and pedigree which rendered him suitable to be king. His right to rule was not secure, as his grandfather had usurped the throne only two decades before in 1399. As Henry's indisputable lineage was so essential to his position, it was portrayed (and embellished) in a number of elaborate genealogical rolls produced throughout his reign, which traced his descent all the way back to Adam and Noah in the Bible. A considerable number of these manuscript rolls survive today, housed in archives, libraries, and private collections all over the world.

As Henry's reign descended into chaos and civil war in the 1450s, these genealogical rolls took on a heightened significance. They were adapted first to reinforce Henry's kingship at its weakest moments, and then later edited to support the claims of his Yorkist rivals. These rolls provide a new lens for considering the dynastic drama that underlay the Wars of the Roses, and to consider how people in fifteenth-century England responded to a changing and volatile political landscape. By using new technologies, digital history and scientific techniques, our project, Wars in the Workshop, aims to bring together these objects from archives across the world to gain a better understanding of Henry VI’s reign.

Henry VI becomes king

On 1 September 1422, Henry VI became king of England, following the premature death of his father, Henry V. At only nine months old, he was – and remains – England's youngest ever king. As he was far too young to take an active role in ruling, the task was delegated to others. Henry's subjects might have hoped Henry would grow up to be a king like his father, but, even as an adult king, Henry preferred leaving the task of ruling to others.

Under his rule, England faced grave, new challenges, such as the loss of their territories in France and the rise of challengers to the throne. Those closely associated with the regime had to find new ways to shore up Henry's kingship. They may even have used history as a means of supporting his rule...

Dual Monarchy: Legacy of Henry V

‘Henry the Sext, of age ny fyve yere ren, Borne to be kyng of worthie reamys two.’

– John Lydgate, The Title and Pedigree of Henry VI1

As a consequence of Henry V’s efforts at war and diplomacy in France, Henry VI was recognised as king of both England and France before his first birthday, succeeding from his French maternal grandfather, Charles VI.

© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, terms of use: CC-BY-NC 4.0.

This French title did not come without problems. The Treaty of Troyes (1420) had effectively disinherited Henry’s uncle, Charles VII, but he was supported by some powerful allies, notably Joan of Arc.

The Lancastrian government in France made efforts to rally support for the Dual Monarchy, both in France and in England. One such effort was a verse chronicle with an accompanying genealogical diagram showcasing Henry VI's descent from St Louis of France through both of his parents.2 One well known example of this diagram is British Library, MS 15 E VI f. 3.3

Nevertheless, the English hold over France was waning, even after Henry was crowned king of France in Paris in December 1431. Piece by piece, the English would lose their conquered territories in France.

From Jean de Wavrin, Anciennes chroniques d'Angleterre (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Français MS 83, f. 205r).

Source: gallica.bnf.fr

Genealogical rolls

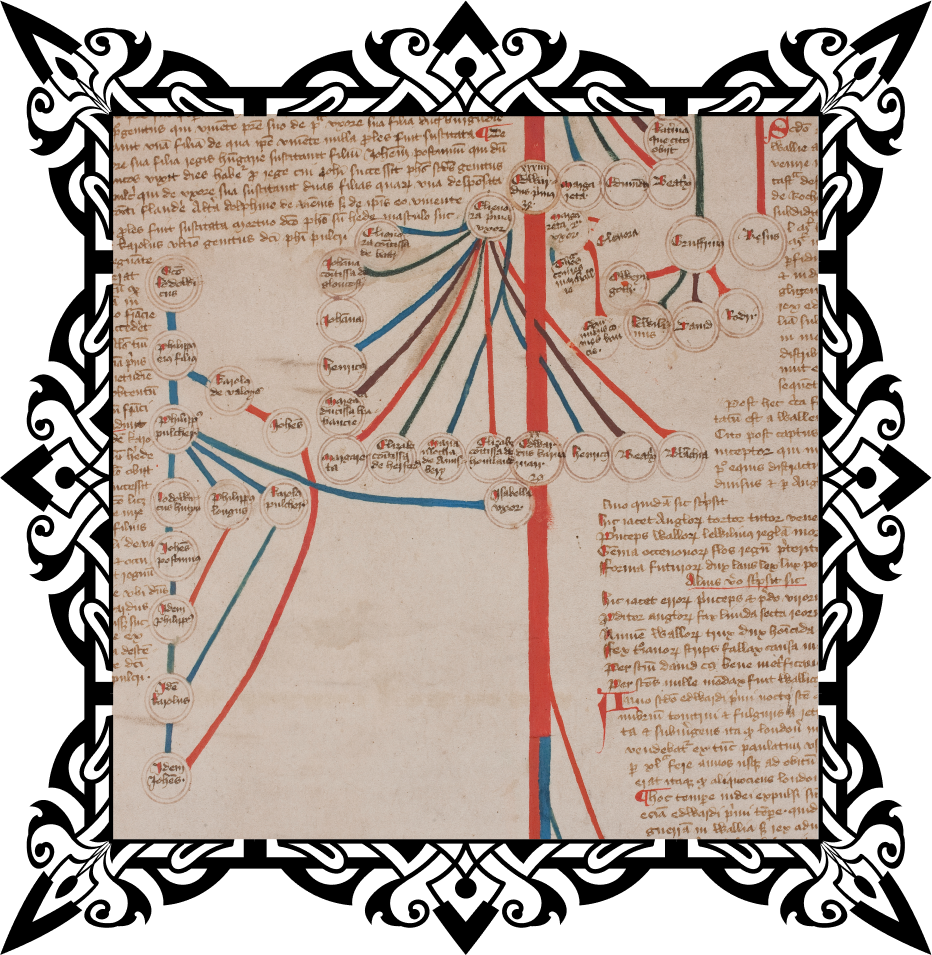

A genealogical roll is a type of manuscript roll which primarily features a genealogy, often as a diagram.

This was a popular way of depicting one's lineage, but genealogical rolls were also increasingly used in late medieval England to depict national history.1 The representation of history as one long, unbroken line had a potential ideological imperative: it legitimised the present by tying it directly to the past, while cleverly smoothing over the cracks of any past ruptures.2 This was especially important for English history which had witnessed major dynastic and cultural changes, like the Norman Conquest.

Image reproduced with kind permission of The Provost and Fellows of The Queen’s College, Oxford.

Forging a biblical connection

Traditionally, English royal genealogical rolls traced a king's descent back to William the Conqueror or further back to Egbert or Alfred.

However, in the fifteenth century, new models of royal genealogical rolls were produced, tracing the king’s descent as far back as Adam or Noah.

The composers of these genealogies were able to trace the royal line that far back through piecing together existing royal genealogical traditions. The connection between Noah and Brutus of Troy, legendary first king of Britain, was made through adapting Welsh royal genealogies.3 English kings traditionally traced their descent from Noah via Woden (or Odin).4 Using both of these descents, the fifteenth-century genealogical rolls could incorporate popular British kings, like king Arthur, into the genealogy, despite these kings having no actual genealogical connection with Henry VI.

Reproduced by permission of the Provost and Fellows of Eton College.

© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, terms of use: CC-BY-NC 4.0.

How the rolls were produced

Despite the large numbers of surviving manuscripts, it is uncertain who produced these manuscripts or where they worked. Despite their anonymity, evidence of their work remains visible on the rolls themselves.

The genealogical rolls were likely produced by professional craftspeople, working on commissions from paying customers. These craftspeople often collaborated, either within a shared workshop or in their own workshops. Production was likely supervised by a stationer, who arranged the commission and oversaw the work.5

The process of making the rolls began with the diagram being sketched out and painted on separate membranes of parchment, using either calfskin or sheepskin. The scribe then filled in the diagram and copied out the text on the membranes, working from a set exemplar.6 Illustrations were traced onto the roll and then the membranes were attached together with glue. If the roll’s commissioner wanted the roll to be further decorated, they could commission artists to paint and illuminate the roundels, add border art, and to add painted initials. Some manuscripts were not decorated in this way, suggesting they may have been left unfinished or their earliest readers perhaps wanted to save money.

Some scribes appear to have specialised in producing genealogical rolls with their handwriting identified on multiple manuscripts. Other scribes appear to have only worked only on the one roll. Some scribes even shared the work and took turns, perhaps to ensure a faster output (and fewer hand cramps!).

How the rolls were read

There has been some suggestions about how the rolls were read, including people displaying them on walls. However, at roughly 18-24ft in length, these rolls would have required very high walls! It would also have made it very difficult to read the content at the very top of the roll.7

It has been suggested, more plausibly, that the rolls were displayed over a table, perhaps in a noble or abbot’s great hall, with people gathering around to look at the roll. This would have been a much more practical (and sociable) way of reading the rolls.

At an average width of 30-40cm, these rolls were relatively easy to handle. People could have read the rolls by themselves, poring over them in their free time. Yet the rolls were considerable status symbols and were worth bringing out to show off to guests: imagine saying you held the entire history of the world in your hand!

The 'Noah' Genealogies

At some point between 1429 and 1438, a new royal genealogy was commissioned for the king, tracing Henry's descent from Noah.1 These genealogies averaged about 18 foot in length and provided a long view of English history, from the Flood to the arrival of Brutus and then all the way down to Henry VI.

Reproduced by permission of the Provost and Fellows of Eton College.

© University of Canterbury

This type of genealogical roll, commonly known as the ‘Noah' genealogies, proved to be rather popular with fifteenth-century audiences. We have identified at least twenty surviving manuscripts which belong to this group. The genealogy was popular enough to have encouraged one group of craftsmen to specialise in its production, following a set design which included ending with a stylised ‘H' initial and illustrations of Lucius (legendary first Christian king of Britain) and St Augustine.

One scribe appears to have been responsible for copying at least fourteen manuscripts. This scribe appears to have begun producing ‘Noah' genealogies before 1438, but was still actively producing the rolls after 1443 when the genealogy was updated to include the new archbishop of Canterbury, John Stafford.

One of the most notable aspects of the ‘Noah’ genealogy is its careful depiction of the past. The rolls make no mention of how Henry VI's grandfather, Henry IV, deposed Richard II to become king. It also left out the Mortimers, who descended from an older son of Edward III (see the family tree below). The compiler of the ‘Noah' genealogy drew attention away from the issue by describing instead the situation in Wales after Edward I's conquest and the Glyn Dŵr revolt. Despite the ‘Noah' genealogy side-stepping the issue, the question of Lancastrian legitimacy and the Mortimer claim would emerge again during the Wars of the Roses...

One family that was not excluded from the ‘Noah' genealogy was the king's Beaufort cousins. The Beauforts were the children of John of Gaunt and his third wife, Katherine Swynford. They were part of the wider Lancastrian family, but were originally illegitimate and disbarred from inheriting the throne by an act of parliament. Nevertheless, they were given a prominent place on the ‘Noah' genealogy. Several roundels were included for Joan Beaufort’s children, but only two of her sixteen children were typically named, Richard Neville, earl of Salisbury, and Robert Neville, bishop of Salisbury and later bishop of Durham.

As well as depicting his claim to England, the ‘Noah’ genealogies also depicted Henry VI’s claim to France from Edward III. Henry’s claim to be king of France came from the Treaty of Troyes, but the ‘Noah’ genealogies instead depicted the dynastic claim Edward III had used to kick-start the Hundred Years War in 1337. Some of the genealogies, like the Canterbury Roll, further emphasised this claim by depicting the central line as being quartered after Edward III – using both red and blue.

© University of Canterbury

The King's Personal Rule (1437-53)

Around 1437, Henry began to take a more active role in ruling. People might have expected him to follow in his dynamic father’s footsteps, but the younger Henry had other ideas. He was disinterested in warfare, focusing less on the ongoing war with France and more on founding educational institutions like King’s College Cambridge and Eton College.

He was keen to secure peace with France, but not always on terms that suited the English.1 The saintly reputation he gained after his death may have been the work of later Tudor hagiographers, but Henry appears to have been genuinely pious in his lifetime.2 He was overly generous, easily swayed, and he did not always have the best foresight – once giving out the same grant to two rival petitioners.3

While a pious and pacifist king might sound good on paper, it did cause some problems. The rapid loss of French territories, economic recession and rising disorder only led to dissatisfaction among the broader population. A number of complaints was made in the late 1440s about Henry, noting his child-like appearance and calling him a ‘natural fool'.4 Much of the popular anger was not directed towards Henry, but towards his favourites, like the duke of Suffolk, who were blamed for misleading and profiting from the king.

The crisis of Henry’s poor leadership came to a head in 1450, spurred on by the loss of Normandy in late 1449. Popular criticism against the regime turned into mob violence with some of Henry’s advisors, like Suffolk, being brutally murdered. Unrest was widespread. The people of Kent and the south-east, under Jack Cade, rose up and marched on London. 1450 was a difficult year for all, but Henry's rule weathered this particular storm.

York and the early 1450s

However, out of the ruckus of 1450, emerged Richard, duke of York, Henry VI’s cousin. Following the death of Henry's uncle, Humphrey, duke of Gloucester in 1447, York had a good claim to being considered Henry's heir, given that Henry had no children or siblings at the time.

York could claim to be Henry's heir as he descended in the male line from Edmund, duke of York, the fourth son of Edward III. York could also claim descent from Edward’s second son, Lionel, duke of Clarence, through his mother, Anne Mortimer. The question of whether a claim to the throne could descend via a woman (or even be claimed by a woman!) was a divisive topic in the fifteenth century, but York would base his later claim to the throne on his Mortimer claim.1

© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, terms of use: CC-BY-NC 4.0.

1453 and the Wars of the Roses

The crisis of 1453

In August 1453, Henry collapsed into a stupor and was no longer able to rule.

Without a clear adult heir to take charge, it was difficult to know how to proceed. Queen Margaret gave birth to a long-awaited son, Edward, in October 1453, but he was far too young to be of any use. York used the situation to his advantage. He had his rival, Edmund Beaufort, duke of Somerset and Henry's current favourite, imprisoned in the Tower. Margaret attempted to secure the regency on behalf of her incapacitated husband and son, but her efforts were rebuffed. York was eventually named Lord Protector, but his attempts at reform were hindered by the violent outbreak of noble feuds.

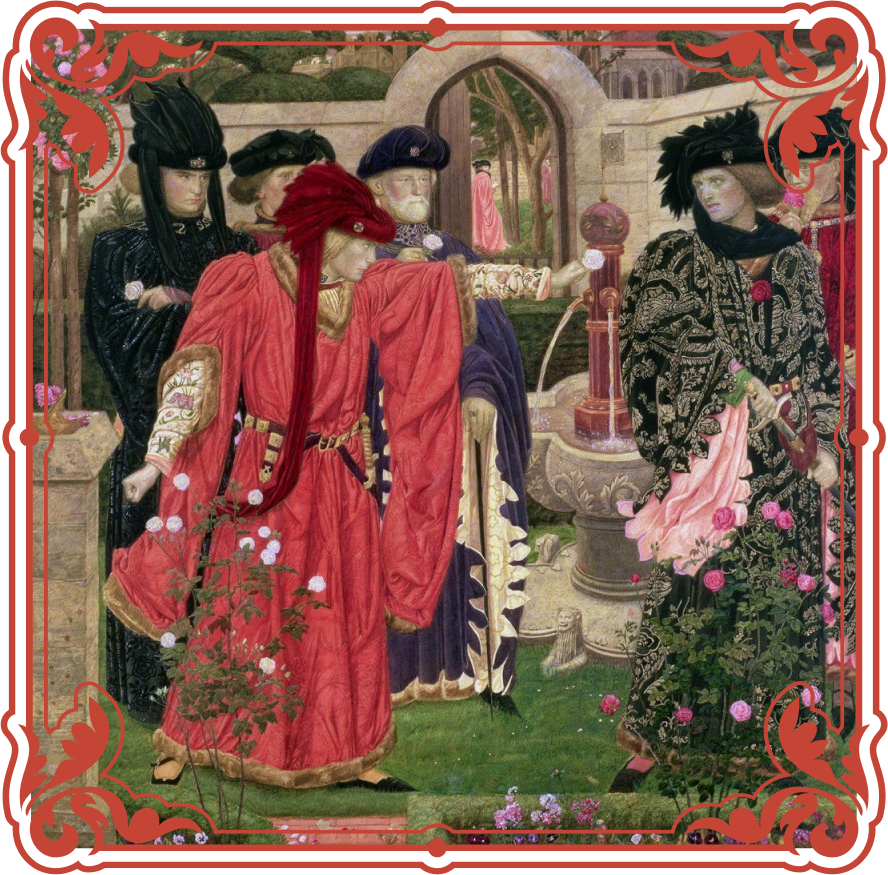

The Wars of the Roses begin (1455-59)

Prick not your finger as you pluck it off,

Lest, bleeding, you do paint the white rose red,

And fall on my side so against your will.– Henry VI Part 1, Act 2, Scene 41

In February 1455, Henry was well enough to take charge again, and York resigned as Lord Protector. Henry was quick to reverse some of York’s decisions, restoring Somerset to his former position as chief adviser.2

Fearful of Somerset’s retaliation, York and his Neville allies, the earls of Salisbury and Warwick, raised an army and marched south. They were met by the king’s army at St Albans on 22 May 1455. Negotiations failed and a bloody battle commenced in the streets. Somerset was killed in the fighting, as was Henry Percy, earl of Northumberland. The king was captured and taken to London by the victorious Yorkist lords.

Parliament was summoned and the Yorkists were pardoned for their actions against the king’s so-called ‘evil councillors’. York was made Lord Protector again, but his second Protectorate came to an abrupt end in February 1456 when his push for further reforms was met with opposition from the lords in Parliament.

The king was nominally in charge again, but, following Somerset's death, Queen Margaret took a more active political role in guiding her husband and son. Following outbreaks of violence in London, she moved the court to Coventry and began building up an affinity for her son, Edward, prince of Wales.

Meanwhile, the sons of those killed at the First Battle of St Albans sought vengeance. Henry tried his best to reconcile the opposing sides. He even went as far as holding a Loveday celebration in March 1458 where the opposing sides held hands and walked side-by-side in procession through London. Despite his best efforts, however, this peace proved not to last.

THE ALBAN GENEALOGIES

A new set of genealogies was produced following the First Battle of St Albans (1455), this time tracing Henry VI's descent from Adam. These genealogies have traditionally been attributed to Roger of St Albans or Roger Alban, a Carmelite monk, who lived in London.1 The Roger of St Albans (or Alban) genealogies were much longer than the ‘Noah' genealogies and contained a revised account of English history. This genealogy ended with a snapshot of the royal family as of 1455, with Henry depicted alongside his wife, Margaret, and their son, Edward.

Unlike the ‘Noah' genealogy, the Alban genealogies contained a brief description of each king, discussing their successes (and failures). Henry V was given a stellar write-up with his victories in France listed in full. The compiler seems to have struggled to find much good to say about Henry VI's reign, with his achievements being limited to his two coronations, his marriage and the birth of his son. With only Calais remaining in English control, the English kings' claim to France was simply left out of the genealogy.

A key feature of the Alban genealogy was a new and updated royal genealogy, depicting the noble descendants of kings from Edward I. Over one hundred names were added to the royal genealogy. Some, like the Beauforts, York, and Buckingham, had featured on the ‘Noah' genealogy; they were joined by other nobles associated with the court party in the 1450s, like Viscount Beaumont, the earl of Wiltshire, the duke of Exeter, and the Percy family. What is striking about this revised genealogy is how the nobility were arranged, with no line favoured over the other. Enemies who had recently fought each other in battle were depicted united by family ties. The Alban genealogy presented a united view of the nobility in the late 1450s just at the time when things were falling apart.

1460-1461

1460: Genealogy rewritten

Attempts at reconciling the rival sides failed. The Yorkist lords once more raised armies in 1459, only to be driven into exile. In 1460, from Calais and Ireland, the Yorkist lords returned, defeated a loyalist force at Northampton, and recaptured the king.

York no longer wished to restore the old order or to act as Lord Protector again. For the first time, he publicly promoted his Mortimer claim to the throne, displaying the royal arms of England on his way to London.

If York had hoped he would be welcomed as the new king with open arms, he was to be disappointed. Even his closest allies refused to abandon their allegiance to Henry VI and quarrelled with him over his decision. A compromise was eventually reached with the Act of Accord, an agreement not dissimilar to the earlier Treaty of Troyes. In this Accord, Henry's son, Edward, was effectively disinherited and York named as Henry's next heir.

Various copies of York's claim were distributed following the Accord. One was even written on the back of a

‘Noah' genealogy (British Library, Harley Roll C. 5).

Fortune's wheel (1460-61)

Not everyone was quite so willing to accept this compromise. Queen Margaret and her supporters did not take the disinheritance of Prince Edward.

York and Salisbury marched north to fight the Lancastrian army, but both were defeated and killed following the Battle of Wakefield (30 December 1460).

Margaret and her army marched south where they defeated the Yorkist forces at St Albans and took Henry into their control. The Lancastrian forces then moved onwards to London, however they were refused entry by the Londoners. The Lancastrian army was forced to withdraw.

Without Henry in their control anymore, the remaining Yorkist lords returned to London and March (York's son) was proclaimed as Edward IV by his remaining supporters and by the people of London on 4 March.

His new position as king would be tested at the Battle of Towton (29 March 1461), one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the Wars. It proved to be a decisive Yorkist victory, establishing Edward as king. Henry, now effectively deposed, and his family were forced into exile.

Editing the rolls

The deposition of Henry VI in 1461 meant that the royal genealogy had to be hastily rewritten to suit the new status quo.

Under Edward IV, new genealogical rolls were specifically produced to celebrate the new king’s reign, in English as well as in Latin.1 But some of the Henry VI genealogies were adapted by their owners in response to the change in regime.

The most extensively edited roll was the Canterbury Roll. At some point between 1461 and 1468, a new scribe amended the roll, adding the Mortimer line and extending the Yorkist line. They annotated the roll, calling the Lancastrian kings usurpers. The revised genealogy ended with a large rose for Edward IV and a lengthy paragraph describing his claim to England, France and Castille and Leon (as if England wasn’t enough!).

Other edits were made at later points to the genealogical rolls. During the English Reformation, Henry VIII moved against the cult of Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury who had been martyred under Henry II. In a proclamation made in November 1538, he ordered that Thomas's name be ‘erased and put out of all the books'.2 Some eager sixteenth-century owners did just that, erasing the name of Thomas Becket from their rolls, indicating how the rolls were still being used and read a century after their initial production.

Some genealogies were even extended much later. Oxford, Queen’s College MS 167 was updated under Elizabeth I with an extension made to the royal genealogy, finding ways to add the Tudors to the royal genealogy.

1470-71

Readeption and death (1470-71)

Henry remained hidden by his supporters for the first few years of Edward IV's reign. He was eventually captured in 1465 and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Towards the end of the 1460s, the initial support for Edward IV waned. His former ally, Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, and Edward's brother, George, duke of Clarence, turned against him and allied with Margaret of Anjou in exile. Warwick and Clarence launched an invasion in October 1470 and drove Edward IV into exile. Henry VI was briefly restored to the throne.

Henry's return to power was not to last long. Edward returned, defeated his rivals and took back the throne in April 1471. Henry's son, Edward, was killed at the Battle of Tewkesbury (4 May 1471).

Henry died soon afterwards on 21 May at the Tower of London. In the Yorkist version of events, Henry died of grief at the news of his son's death. It was more likely that he was murdered on Edward's order so as to remove the lingering threat of further Lancastrian resistance.1 His death marked the end of a long and unhappy reign, but Henry's political significance was not to end with his death.

the saintly king

Henry was initially buried at Chertsey Abbey, but under Richard III, he was reburied at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. Following his death, people associated miracles to him and attempts were made under his nephew, Henry VII, to make Henry VI a saint.1

Henry, for all his good qualities, did not prove to be a good king – or at least one politically astute enough to rule effectively. During his reign, his father's conquests in France were lost, his subjects endured economic hardship, and his nobility fought among themselves. Yet, despite his failings, Henry was still able to hold the loyal support of his followers and he remained as king for a remarkably long time (almost forty years). Henry may not have forged a reputation as a good king, but his legacy continues today, if not in his bloodline, then in the institutions that he founded, Eton College and King's College, Cambridge, and in all the manuscripts and art that were produced to support his rule.

The rolls & heritage science

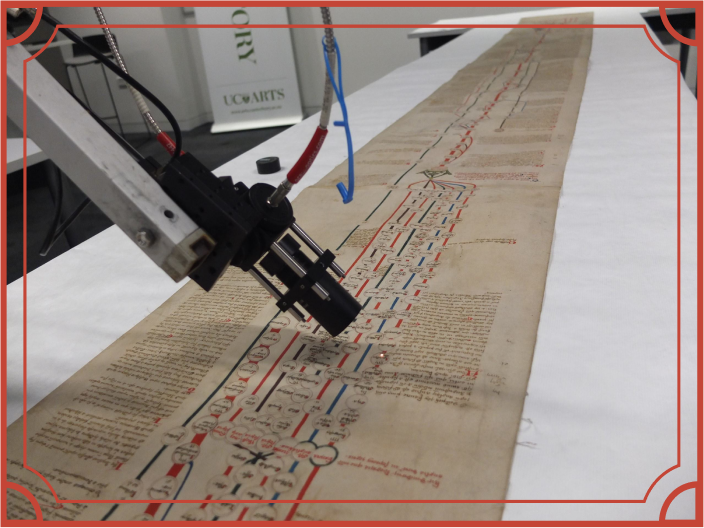

The Science of the Rolls

Developments in science and technology mean that we now have new ways of studying manuscript rolls. Specialist techniques like spectroscopy have provided us with the means of looking at the rolls in ways our eyes cannot, allowing us to see beneath layers of editing to visualise what the manuscripts may have originally looked like.

Digitisation also provides new ways of presenting and analysing data from the manuscripts and allows new audiences to view the manuscripts. Take the Canterbury Roll for example. This manuscript roll in New Zealand can be viewed by anyone in the world, at any hour of the day, all at the click of a button. A digital edition of the Canterbury Roll was released in 2017 by the Canterbury Roll Project team. This edition was especially innovative – tiling multiple images of the manuscript to provide a full view of the roll.1 For more information on the digitisation process, watch this short video.

The work undertaken by the Canterbury Roll Project, following the release of the digital edition, reveals the potential that scientific and digital techniques have for making new discoveries on old, historic objects.

Spectral analysis work was undertaken by the ISAAC (Imaging & Sensing for Archaeology, Art History & Conservation) Mobile Laboratory from Nottingham Trent University in January 2018, bringing their equipment and working with the manuscript in-situ at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand.

The techniques

The ISAAC Lab used various techniques in their analysis of the Canterbury Roll, including:

- Spectral imaging - using their in-house PRISMS camera

- Reflectance spectroscopy

- X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy

For more information on how the ISAAC lab analysed the roll, see this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ISlHohIQlXc

The results

The Ark beneath the Rose

At the very beginning of the Canterbury Roll is a roundel depicting Noah’s Ark, but it has largely been obscured by an editor who painted a large red rose over it.

The ISAAC Lab was able to reveal by spectral imaging the original image of Noah’s Ark.

Noah’s Ark beneath the red rose. Image reproduced with kind permission of the ISAAC Lab.

edits

At some point after Henry VI’s deposition in 1461, a Yorkist editor decided to rewrite history on the Canterbury Roll by grafting on a whole new genealogy for Edward IV. This editor appears to have used a different type of red pigment for their edits. By comparing pigment data, we can distinguish between original features and what the editor added on.

Catherine de Valois?

Besides the Henry V roundel there appears to have been a slight erasure, just about visible to the naked eye. The ISAAC Lab was able to reveal this erasure in closer detail.

Could this section be a reference to Catherine de Valois? Henry VI’s mother features on other genealogies, but mostly those produced following her death in 1437. While an important figure during the early years of Henry’s reign, Catherine’s final years were obscured by scandal. She married in secret a Welsh courtier, Owen Tudor, and had several children with him. Perhaps her name was erased here in response to her scandalous second marriage.

More work to go

There remains a lot more work to do on analysing further genealogical rolls, but the case study of the Canterbury Roll reveals just how valuable scientific techniques can be for our understanding of how these rolls were produced and edited.

As more and more manuscript facsimiles are uploaded online, we need to find new and innovative ways to digitise non-codex objects to make them more accessible and readable for viewers. Rolls can prove to be especially difficult to represent digitally, being exceptionally long (up to 40ft in some cases!) and being tricky to lay flat which can lead to distorted images. By combining the streams of historical research, heritage science and digital humanities we may develop a better framework for digitising existing manuscript rolls, providing more research opportunities for budding researchers and enhancing what we know about the rolls' production and use in medieval society.

Want to learn more?

Check out the Canterbury Roll for yourself – all online! https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/canterburyroll/

Check out the ISAAC Lab website:

https://www.isaac-lab.com/

Read this article

https://www.stuff.co.nz/science/105510416/secrets-of-the-medieval-canterbury-roll